Bridging Borders with Africa: Reimagining FX Settlement Risk with Sika

April 10, 2025

Bridging Borders with Africa: Unlocking USD Liquidity with Juicyway

April 24, 2025Across Africa, the informal economy quietly powers daily life. According to the International Labour Organization, the informal economy employs over 80% of the workforce and contributes more than half of the continent’s GDP. Yet despite its scale and significance, it remains misunderstood, underbanked, and underserved by the financial systems that claim to drive economic growth.

Much of the rhetoric around informality focuses on eliminating or formalising it — often in pursuit of regulation, taxation, or investment-readiness. But what if the better path forward is to recognise it, embrace it, and build around it?

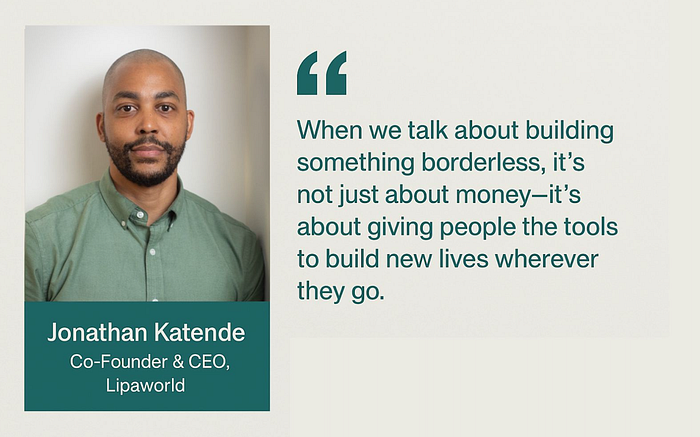

In this third article in our Bridging Borders with Africa series, we explore Pillar 4 of our Five-Pillar Framework: Financial Inclusion & Informal Economy of our Five-Pillar Framework for Cross-Border Payments in Africa. We look at how informality became the dominant economic mode in Africa, why it’s here to stay, and how startups like Lipaworld, led by Jonathan Katende, are creating products designed not just for the formal sector — but for the real economy that most Africans live and work in every day.

What Is the Informal Economy — and Why Does It Matter?

The concept of the informal sector was first introduced by anthropologist Keith Hart in a 1971 study of economic activity in Ghana, where he drew a distinction between formal, regulated economic systems and the unregulated, often overlooked activities that existed outside them. This idea has since evolved into what we now refer to as the informal economy — a broad category encompassing income-generating work that operates beyond the reach of state regulation, taxation, and official statistics, such as market traders, informal transport operators, tailors, hairdressers, and street food vendors.

In the African context, the informal economy is not just common — it is foundational. It underpins livelihoods, sustains local commerce, and provides access to essential services where state infrastructure is limited. A multi-country study across Sub-Saharan Africa found that the informal economy contributes an average of 42.2% to Gross National Income (ILO, 2005; Walter & Walther, 2007). This economy is also profoundly gendered. According to data presented at an African Union meeting in 2008, 84% of women in Africa are informally employed, compared to 63% of men. For many women — especially those with limited access to education, formal employment, or capital — informal work is not just an option; it is often the only accessible path to economic participation.

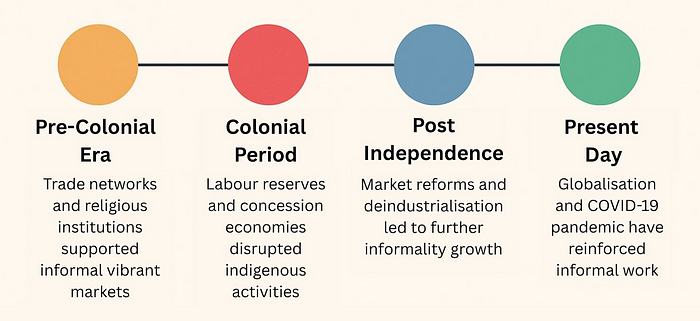

A Brief History of Africa’s Informal Economy

Africa’s informal economy didn’t emerge by accident — it is the product of deep structural forces, shaped by pre-colonial trade systems, colonial disruption, and post-independence policies. In her essay Africa’s Real Economy, Professor Kate Meagher highlights how historical trajectories continue to influence the continent’s economic landscape today.

- In the pre-colonial era, many African societies — particularly in West Africa and parts of East Africa — had developed centralised states and large-scale religious institutions, such as Islam and indigenous oracular systems. These structures provided the institutional support needed for vibrant markets, commercial institutions, and long-distance trade networks.

- During the colonial period, the trajectory diverged by region. Economist Thandika Mkandawire argued that:

◦ In West Africa, particularly in economies built around cash crop exports, colonial systems were relatively more tolerant of indigenous economic activity.

◦ In Southern and Eastern Africa, by contrast, indigenous enterprise was actively suppressed. These regions were often transformed into labour reserves — areas where Africans were pushed into working as cheap migrant labour in mines, plantations, farms, and urban centres.

◦ In Central Africa, indigenous activity was also constrained through the use of concession economies, particularly in countries like the DRC and Gabon. Under these systems, foreign companies and individuals were granted exclusive rights to extract and profit from natural resources, often enforced through forced labour and violent control. - Following independence, many countries retained regulatory systems inherited from their colonial administrators. In some cases — such as Mozambique, Angola, Zambia, and Zimbabwe — war, political instability, or economic collapse pushed even more people out of formal employment and into informal livelihoods.

- In the present day, globalisation and market liberalisation have had a homogenising effect on African economies, yet formal job creation has lagged behind. Informality has grown even further, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, which triggered a sharp decline in demand, disrupted supply chains, and dried up liquidity for many small businesses.

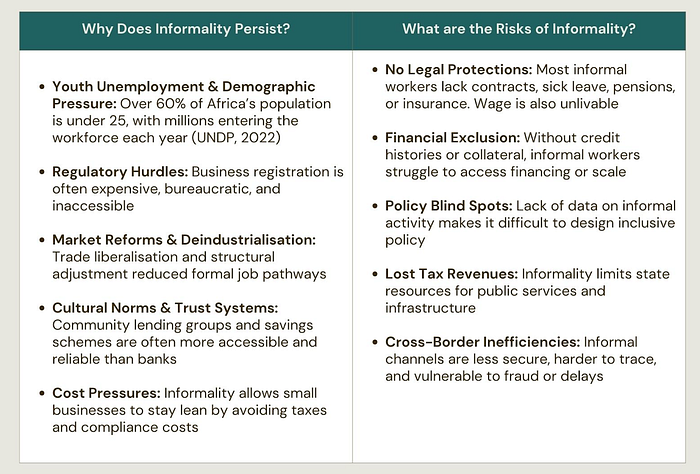

Why Informality Persists — and the Risks It Brings

Despite its scale and resilience, informality is often misunderstood. It’s not a temporary fix or a sign of chaos — in many African markets, informal systems are highly organised, efficient, and deeply embedded in local economies.

In South Africa alone, the informal economy is estimated to be worth over R750 billion (≈ $39.75 billion) annually, spanning spaza shops, street vendors, and backroom rentals (BusinessTech, 2024). As GG Alcock, a leading expert on South Africa’s informal economy, notes:

“Just because it’s informal doesn’t mean it’s unstructured. It’s a vibrant, deeply organised economic system — just not a formal one.”

These systems thrive not only out of necessity, but because they offer adaptability, trust, and speed in environments where formal systems may be rigid, exclusionary, or underdeveloped. Informality reflects both the structural barriers that push people out of formal channels, and the entrepreneurial ingenuity that fills those gaps. But it also comes with real trade-offs — from limited worker protections to inefficiencies that ripple through national economies.

To better understand its persistence and implications, the table below outlines the key drivers of informality alongside the risks it creates for inclusive economic development.

Informality may be a rational response to systemic barriers, but its risks — especially around exclusion and inefficiency — must be addressed by any serious financial solution.

Cross-Border Payments in an Informal Economy

We’ve established that Africa’s informal economy is massive — employing over 80% of the workforce and contributing more than half of the continent’s GDP (International Labour Organization). In Sub-Saharan Africa, the impact is even more pronounced, with studies estimating that 30–40% of trade occurs informally. Efforts such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) are working to bring more of this activity into the formal fold by simplifying trade regulations and reducing barriers. But these initiatives are still in their early stages, and informality remains the dominant mode of commerce for millions across the continent. This reality has significant implications for how money moves — especially across borders.

Barriers to efficient cross-border payments in the informal economy include:

- Exclusion from formal channels: Many informal workers operate outside the formal financial system. They often lack the IDs, documentation, or digital tools required to access regulated cross-border services. This challenge is especially acute for migrants, refugees, and residents of informal settlements, who face added exclusion due to legal status, mobility, or lack of fixed addresses.

- Fragmented and unregulated networks: Without access to formal remittance infrastructure, informal actors often rely on cash couriers or unregistered agents. These channels can be opaque and high-risk, offering little standardization or consumer protection.

- Underserved population corridors: Large volumes of cross-border economic activity — especially among informal traders and seasonal workers — go unrecorded. As a result, these high-need corridors are often overlooked in the design of payment infrastructure, leaving users with few or no formal options.

- Security and efficiency risks: Informal cross-border payments are frequently vulnerable to theft, fraud, and delays. With no tracking systems, dispute resolution, or legal recourse, users bear the full risk of transaction failure.

Given the sheer scale of these limitations, any payment solution targeting African markets must start by acknowledging how people already move money outside of financial institutions.

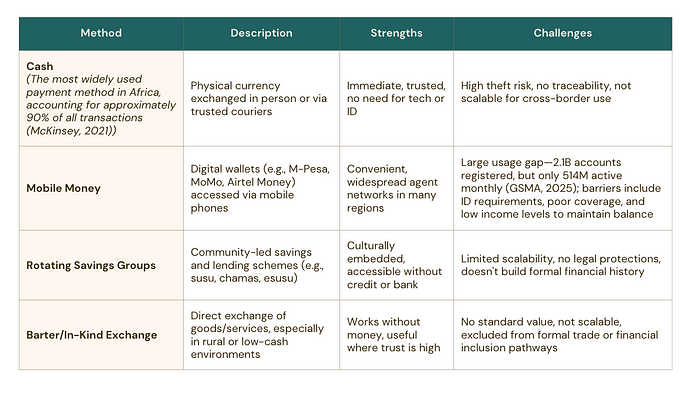

Payment Methods in Africa — Their Strengths and Challenges

While the informal economy is here to stay, the systems people use to move money are fragmented, high-risk, and largely invisible to regulators and policymakers. For any cross-border payment solution to succeed in Africa, it must not only acknowledge these informal realities — but design with them in mind.

Introducing Lipaworld: A Borderless Financial Platform for the Underserved

Co-founded and led by Jonathan Katende, at first glance, Lipaworld may resemble a typical remittance platform. But its core innovation lies in how it reimagines cross-border payments — not just for migrants and freelancers navigating rigid financial systems, but for the informal economy, which remains largely excluded from global finance.

Lipaworld recognises that Africa’s informal economy — estimated at $684 billion — is both underserved and overlooked. Informal traders, vendors, and rural communities face systemic barriers to receiving money securely, efficiently, and transparently.

This exclusion extends to remittances. While the formal market processed $111 billion in 2022, the informal remittance market is estimated to be 1–3 times larger, meaning an additional $111–$333 billion may be moving through unregulated channels (FT Partners, 2023). Lipaworld bridges this gap by enabling cross-border payments that work with informal infrastructure.

Key Features include:

- Digital Voucher Marketplace: Enables senders to purchase and redeem vouchers for essentials — groceries, school fees, airtime, utilities — ensuring funds are used as intended while reducing fraud.

- Borderless Payments: Supports fast, affordable transactions in multiple currencies and stablecoins (ZAR, ZWL, NGN, KES, GHS, USD), with payouts delivered via local payment methods such as mobile wallets and agent networks.

- Onchain Banking: Provides secure, low-cost financial banking services via blockchain — no bank account needed.

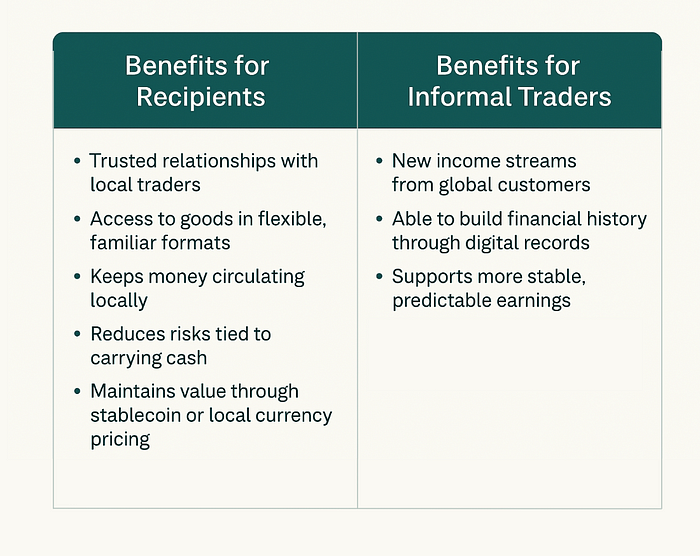

- Designed for Informal Markets:

◦ What sets Lipaworld apart is its voucher infrastructure — built to reach users with limited digital access. Vouchers can be delivered via SMS, WhatsApp, printed codes, or trusted intermediaries, making them usable even in low-connectivity areas.

◦ They’re redeemable at over 200,000 informal traders — from market stalls to roadside vendors — who are equipped with POS systems and are incentivised after each transaction.

◦ This model benefits both sides:

By targeting both the consumer and merchant sides of financial inclusion, Lipaworld builds from the ground up — aligning with how people already earn, trade, and survive. In doing so, it offers a more inclusive blueprint for cross-border payments: one that is local, trusted, and designed for the realities of Africa’s informal economy.

In Conversation with Jonathan Katende, CEO of Lipaworld

What inspired you to start Lipaworld?

The idea came from a personal pain point. As an immigrant in the U.S., I wanted to send money home in a way that was purposeful, secure, and cost-effective. But some of my family members live in rural areas without access to traditional financial services — and some are undocumented or lack formal data profiles. I realised there was a gap in the market for a solution that could reach these people. That’s why I built Lipaworld: a platform that moves value through gift cards and vouchers, not just cash, and that truly considers the realities of underserved communities.

Where do you see Lipaworld heading in the coming years?

We’re building Lipaworld to become the borderless wallet for immigrants — a platform where people can earn, spend, and send from anywhere in the world. We see our evolution across three key pillars:

- Everyday banking services to store, manage, and move money without needing a traditional bank account

- Onchain financing and stablecoins for fast, p2p low-cost transfers

- A global marketplace where users can send essential goods and services to loved ones, while supporting local merchants that are robustly vetted by us.

Our goal is to give people the tools to build financial lives that are flexible and mobile — especially those who move not by choice, but by circumstance e.g. war or regulatory changes.

What’s the biggest misconception about the problem you’re solving?

That Africa is already fully digital. It’s not. Cash is still heavily relied on, and the informal economy — representing over 80% of the workforce — isn’t going anywhere. Many solutions are designed with the assumption that everyone is online or has access to formal tools, but the reality is very different. Not everyone can afford tech. Not everyone is documented. You have to meet people where they are.

For me, this is also personal. I left the DRC with my family and ended up in South Africa. What we thought was a temporary stop became home. I had to learn the language, adapt to a new culture, and watch my parents do the same under much harder conditions. When I later moved to the U.S., I didn’t have to learn a new language, but I still had to build credit and navigate an unfamiliar financial system. So when we talk about building something borderless, it’s not just about money — it’s about giving people the tools to build new lives wherever they go. It’s about offering a head start: a way to adapt, find stability, and begin again — whether by choice or by necessity.

What advice would you give to other fintech founders building in this space?

Be clear on your mission — but flexible in how you get there. This is a seven-day-a-week journey. You have to really believe in what you’re building because the tough days will test your resolve. For me, it’s personal — I know this solution helps people like me and people I love. That keeps me going.

Are there other regions solving similar problems in ways you admire?

Yes. I think the way South Africa has embraced stablecoins and neobanks is really promising. I’m also inspired by what’s happening in Brazil and Argentina — markets that have had complex economic histories, but are now finding ways to make Web3 work. They show that with the right infrastructure and mindset, new models can thrive — and Africa has that same potential.

What are your thoughts on Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) and its role in cross-border payments?

In theory, PAPSS is a great initiative. But in practice, I worry it still reinforces legacy systems by favouring traditional banks. If we really want to transform cross-border payments, we need to include tech-first businesses and work towards standardised regulation that opens the space to innovation.

What ecosystem-level changes would help startups like yours succeed?

Aside from regulatory clarity, we need bolder investors. Right now, many are focused on de-risked, “safe” bets. But Africa is still early — this is the time to test new models and fund ambitious ideas. We need more investors who are willing to back innovation at the edge, and who are serious about building ecosystems, not just portfolios.

Final Thoughts

The informal economy isn’t a fringe issue — it’s the core of Africa’s real economy. As we build financial infrastructure across the continent, it’s not enough to digitise what’s formal. We must design for the people and systems that already work, even if they sit outside the spreadsheet.

With over 90% of retail transactions in Africa still conducted in cash (McKinsey, 2021), the informal economy isn’t going anywhere.

Solutions like Lipaworld prove that meaningful innovation doesn’t require replacing these systems — it requires meeting them where they are. By designing with empathy and realism, startups like theirs are bridging not just payment gaps — but cultural, geographic, and economic divides.

Here’s how you can support their mission:

- Learn more and follow their journey at lipaworld.com

- Explore how their solution is transforming cross-border payments

- Share this story with anyone working on financial inclusion, remittances, or the informal economy

If you know of other startups tackling cross-border payment challenges in Africa, I’d love to hear about them. And I’d also love to know — what do you see as the biggest barriers or opportunities in this space? Feel free to drop a comment or reach out directly.

About the Author

Victoria Olayide Adesanya is an emerging fund manager with over a decade of experience in finance. She has advised leading investment banks like Morgan Stanley and held roles at Credit Suisse and Barclays. As an active angel investor, venture partner and advisor, Victoria supports startups focused on financial inclusion and cross-border payment challenges in Africa. Based in New York City, she holds a First Class degree from the University of Nottingham and is a CFA charterholder.

Get the Latest from Bridging Borders with Africa

Be the first to read our in-depth analysis, founder interviews and cross-border fintech insights.